Dentists on the front lines

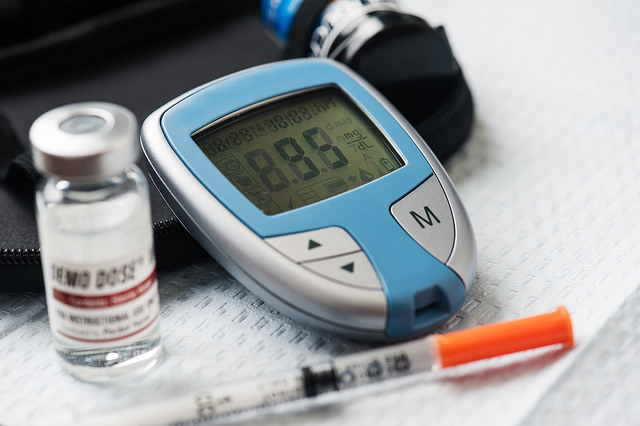

Dental student Keith Mahipala could see all the signs. The diabetes risk assessment raised suspicions, but it was the blood sugar and blood pressure readings that bolstered his concerns. At the patient’s first screening appointment, the display on the glucometer flashed 100 milligrams. This placed her just on the cusp of prediabetes, which ranges from 100 to 125 mg per deciliter. What’s more, a chronic lack of sleep, self-medicated with coffee and 5-hour Energy shots, caused the patient’s blood pressure to spike – and stay there. Mahipala had hoped to get her blood sugar reading during a subsequent appointment, but he never got that chance.

“I had to dismiss her the last time we visited because her blood pressure was consistently high,” says Mahipala. Medical clearance must be received before treatment can resume.

“When she returns, hopefully she has taken into consideration what we talked about regarding her sugar intake and how that could also affect our treatment plan,” says Mahipala. This delicate dance is one that occurs during a staggering number of appointments at Texas A&M College of Dentistry. Only two groups don’t automatically take the diabetes risk assessment: those age 39 and younger, and those already diagnosed as diabetic.

The word “epidemic” is largely relegated to the realm of infectious disease, describing the sudden increase in the number of cases above the norm for a specific population or region. Now health care professionals have coined a new usage for the term.

“With the prevalence of diabetes approaching 10 percent of the U.S. population, many organizations have classified diabetes as an epidemic,” says Dr. Brent Hutson ’93, associate professor in restorative sciences, who spends one day a week treating medically complex patients at the Charles A. Sammons Cancer Center, and the remainder of the time supervising students in the College of Dentistry’s clinics.

In the mid-1990s, around the time Hutson finished his dental degree, about 6 out of every 100 adults in the state had diabetes. Two decades later, the number has nearly doubled to approximately 11 out of every 100 Texans.

What’s important to note is the type of diabetes under scrutiny. Type 1 diabetes, which requires daily insulin injections, is not preventable. Type 2 diabetes, commonly a result of inactivity and excess weight, is the form that is rising — and with it, our health care costs — as a host of other conditions accompany the metabolic disorder, ranging from high blood pressure and stroke to kidney disease and nerve damage. Type 2 diabetes doesn’t just affect people in their 40s or 50s. Even children are susceptible.

And in the dental school’s clinics, diabetes is unfortunately becoming a norm, not an exception.

“I graduated in 1993 and distinctly remember only having two of my assigned patients taking any medication on a regular basis, and did not have a single diabetic patient,” Hutson says. “Today as I work with students in the clinic, nearly all of our patients are taking multiple medications.”

Simply calling up a search on the college’s axiUm electronic patient records system reveals an unsettling reality. Between January 2014 and March 2016, 11.4 percent of patients described themselves as diabetic during their screening appointments.

Determining risk is only half of the battle. Once dental students and faculty have identified at-risk patients, how do they ensure patients get the help they need? The first step: Referring patients to a physician when they screen high on the diabetes assessment.

“This way, students are introduced to medical screenings and referrals as soon as they start patient care,” says Dr. Andreea Voinea-Griffin, research assistant professor in public health sciences. In some cases, like that of Mahipala and his patient, the student may opt to test blood glucose levels.

At the College of Dentistry’s community clinic sites, such as North Dallas Shared Ministries, screening is taken a step further. Dental assistants and dental students at the clinic screen for diabetes and administer a glucometer test for walk-in patients. At-risk patients will receive referrals to the clinic run by UT Southwestern Medical School, and their total health will be tracked over time so that students and faculty from both institutions can gauge outcomes.

Grappling with diabetes – be it in preventive measures or diagnosis – is propelling dentists and physicians into closer partnership.

“As physicians, we are very excited to collaborate with dentists on screening patients for diabetes,” says Dr. Lydia Best, medical director of the Diabetes Health and Wellness Institute, affiliated with Baylor Scott and White Health and located near Dallas’ Fair Park.

“Currently there is some encouragement from different medical and dental authorities for dentists to perform office testing to identify and refer patients with diabetes. Likewise, primary care providers are encouraged to screen for periodontal disease and refer patients to the dentist and hygienist.”

As a part of routine patient wellness visits at the diabetes center, Best says physicians check for signs of oral cancer, severe tooth decay, periodontal disease and acute infection.

It seems as medical and oral health professionals strive to steer patients on a course free of diabetes, they are realizing a united front carries far more impact than separate, solitary advances.

“As physicians, we are very excited to collaborate with dentists on screening patients for diabetes.” – Dr. Lydia Best, Diabetes Health and Wellness Institute

Having diabetes doesn’t mean an immediate sentence to a lifetime of dental problems. Dr. Terry Rees, director of the Stomatology Center at the College of Dentistry, oversees a program in which 14 percent of patients have diabetes listed in their medical histories.

“Our patients are older, and consequently, a significant portion of them are diabetics,” says Rees. “Many of these are well controlled, and there’s not much of an additional problem with that particular group.”

The key is long-term management. If the blood sugars are kept in check, symptoms stay at bay. The undesirable alternative: uncontrolled diabetes.

“A lot of our patients are diabetics and don’t know it or haven’t been tested yet,” Rees says. “With those folks we see things like burning mouth syndrome,” in which a burning sensation occurs on the tongue and sometimes lips, often spontaneously and without an exact known cause. “There is one school of thought that burning mouth is caused by neuropathy,” Rees continues. In diabetics, this form of nerve damage can cause numbness, and pain and weakness in the limbs, but the digestive tract can also be affected.

“Diabetic patients are also going to have reduced salivary flow,” Rees says, “and that causes an amazing amount of discomfort. It is surprising what a growing number of patients are here because of dry mouth.”

Other telltale signs run the gamut from delayed healing, yeast and fungal infections in the mouth to mucosal lesions and periodontal disease with distressingly rapid progression.

“When we see that, we query the patients,” says Rees. A questionnaire is given, and the center has the capability to perform blood glucose and A1C tests, which reveal average blood sugar levels over a three-month spread.

“If the results confirm Stomatology Center faculty members’ suspicions, we give them a copy of the test results and encourage them to see their physician and take along the information from the test,” says Rees.

“If the results confirm Stomatology Center faculty members’ suspicions, we give them a copy of the test results and encourage them to see their physician and take along the information from the test,” says Rees.

“We never tell the patients that they are diabetic. We tell them that they have elevated blood sugar and they need to be evaluated by a physician,” he adds. “We have an awful lot of patients in a prediabetic state, and a lot of them will become diabetic.

“When they’re prediabetic, they haven’t had a lot of bad effects yet. Hopefully we can prevent those bad effects.”

Over the long term, the most impactful tool dentists have in combating the effects of diabetes is remarkably simple, according to Hutson.

“The most important intervention we can offer is frequent recalls,” he says. “This affords an opportunity to re-evaluate and address dental issues as they arise.”

Training the next generation of dentists to discuss whole health concerns with patients is crucial, and the conversation isn’t limited to diabetes.

“The great thing about how we are trained here is that we always focus on any systemic issues the patient may have first,” Mahipala says. “We are never focused on the teeth at first. In fact, that’s the last thing we look at. We always need to remind ourselves that there’s a person attached to all those teeth.”

Educating a patient is all too often the easy part. It’s what happens next – action, or in some cases, inaction – that’s the kicker. While some patients seek a physician’s care, make lifestyle changes, and do what is needed to control their diabetes, others do not.

As of early May 2016, Mahipala continues to wait for the chance to once again work with his patient. She still has not returned to the dental school. He hopes he has been able to make a difference, but her absence is a sobering reminder that motivating patients is an individual process.

“We are never focused on the teeth at first. In fact, that’s the last thing we look at. We always need to remind ourselves that there’s a person attached to all those teeth.” – Keith Mahipala, D4

“The education I provide to my patients is vital because most of them don’t see a physician on a regular basis,” Mahipala says.

“Sometimes it’s up to us to point out any risk factors or uncontrolled systemic problems the patient may not be aware of.”

At that point, responsibility shifts once again. The journey to improved health begins with a single step, and only the patient can make that personal commitment a reality.

This article originally appeared in the Summer/Fall 2016 issue of the Dental Journal.