Honored at last

There’s no telling what thoughts drifted through Houston dentist Dr. Ralph Boelsche’s mind as the Texas countryside slid past his sedan’s windows each week.

The experience of navigating U.S. Highway 75 between Houston and Dallas in the mid-1940s was tedious at best.

It was a two-lane highway in those days, which meant inching along behind slow vehicles until it was safe to pass and stopping at traffic lights in sleepy towns along the way.

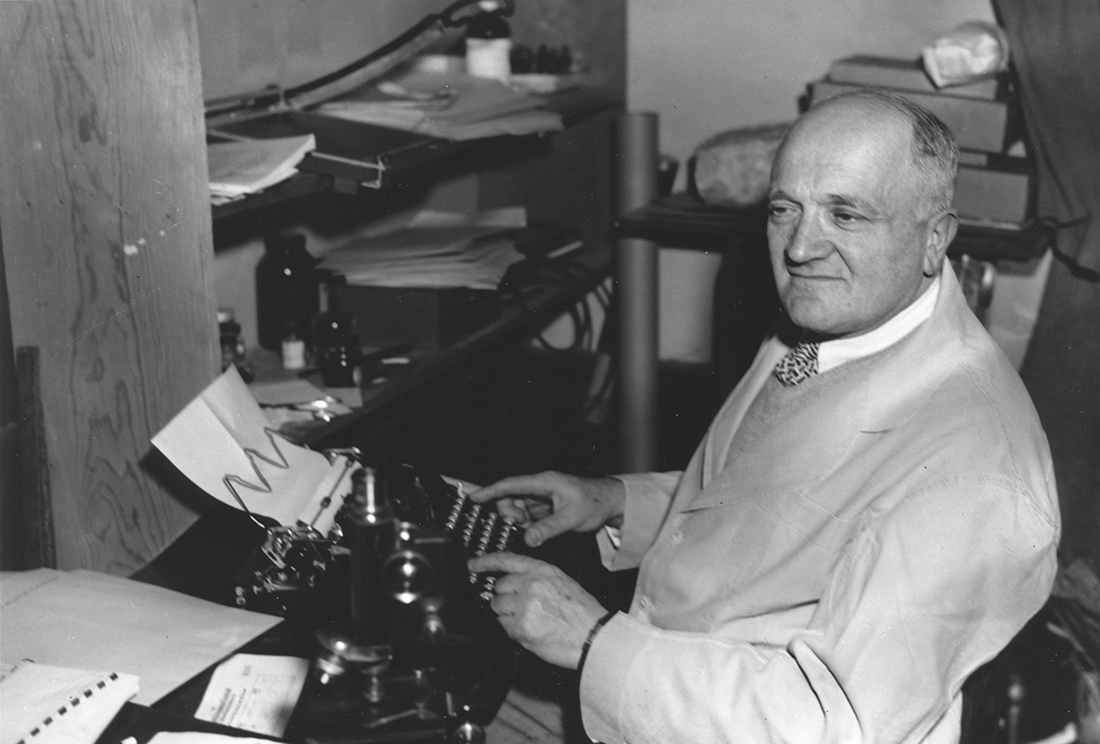

Seventy years later, the details of those 12-hour round-trip treks are lost to time, but the reason for Boelsche’s travel to what was then Baylor University College of Dentistry is coming to the forefront at last: Dr. Bernhard Gottlieb, professor of oral pathology and dental research from 1941 until his death in 1950.

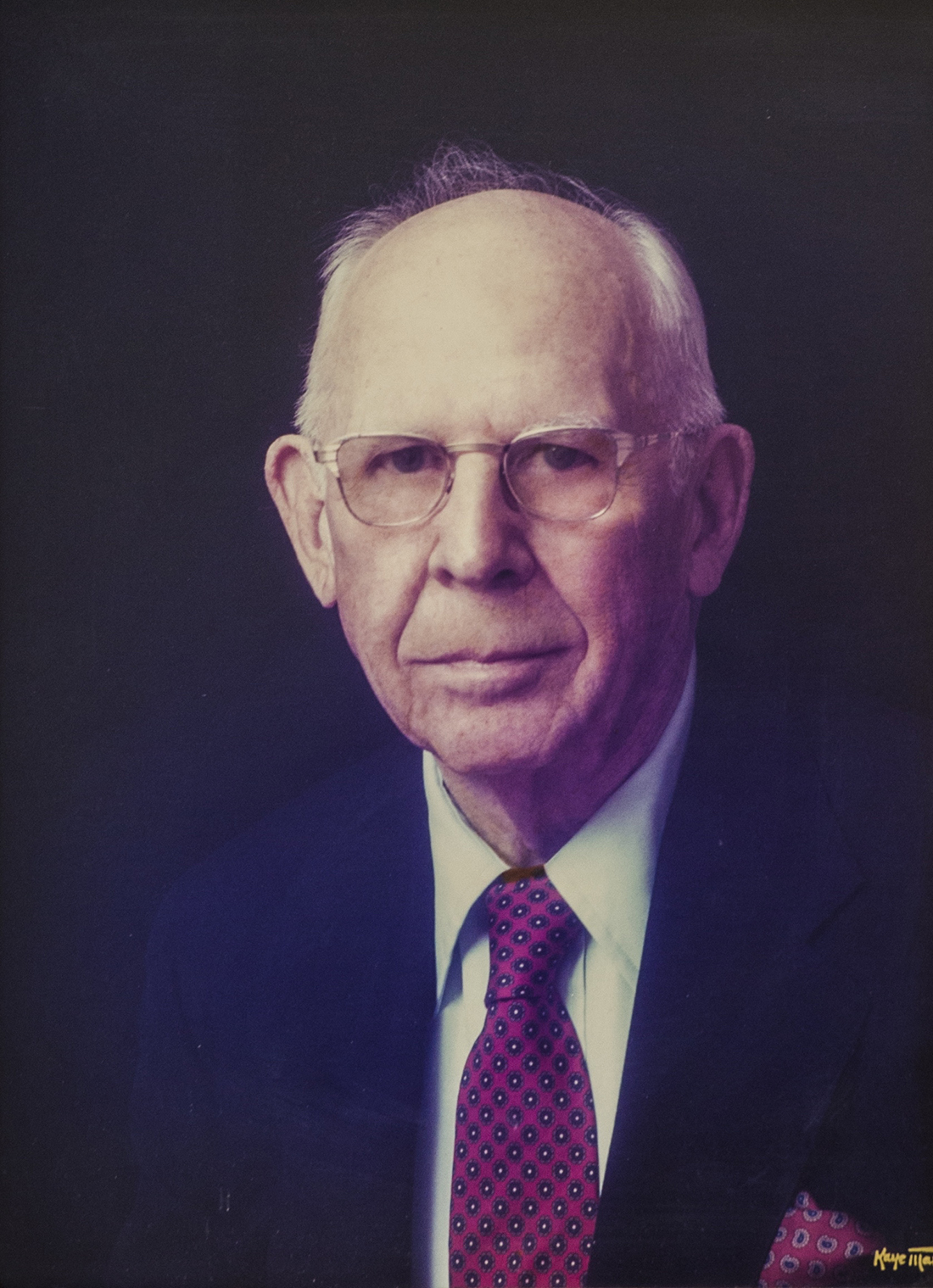

Today a $1 million endowment at Texas A&M College of Dentistry bears his name, due in part to Boelsche’s benevolence.

“Dr. Boelsche talked about Dr. Gottlieb all the time,” says Dr. Frank Eggleston ’70, explaining that his mentor assisted Gottlieb with research on dental caries, the topic of a textbook published by Gottlieb in 1947.

Early in Eggleston’s career and late in Boelsche’s, the two shared office space. There Boelsche kept a portrait of Gottlieb in a cabinet alongside his books; a visual reminder of this eminent scientist.

Boelsche attended Gottlieb’s weekly seminars — which he described as “the most stimulating and informative of his career” — according to a story in the 1985 Baylor Dental Journal. To appreciate Gottlieb’s influence, not only on Boelsche but more broadly on dental science, we must consider his journey.

Austrian beginnings

Gottlieb was a physician with specialty training in dentistry, having received his medical degree in 1912 from the University of Vienna. In the 1920s and 1930s, he headed the Dental Research Institute in Vienna, home to some of the brightest scientists in the world.

“This was a man bigger than life,” says Dr. Thomas Diekwisch, department head of periodontics and director of the Center for Craniofacial Research and Diagnosis at the College of Dentistry. “His vast list of contributions includes all areas of dental research: Endodontics, periodontics and oral pathology all claim him as their ‘father.’

“Gottlieb’s legacy was his role as the father of translational research in dentistry,” Diekwisch continues. “Call it oral pathology, oral biology or translational dental research, Gottlieb combined his knowledge of dental pathology and oral diseases with basic sciences research and clinical dentistry. His greatest contribution to today’s dental research was his mentorship and influence on all the fantastic people who came out of his laboratory in Vienna.”

In a cruel fate of history, World War II fractured this group of scientific colleagues. The anti-Semitism that accompanied Nazi expansionism in the late 1930s shook the institute to its core. After Germany annexed Austria in 1938, the University of Vienna ousted all Viennese faculty members of Jewish descent or ties — an estimated 75 percent of the medical faculty — Gottlieb included. This event ushered many exceptional scientists to the U.S.

Several of Gottlieb’s institute colleagues, household names in dental science — Drs. Balint Orban, Peter Weinmann and Harry Sicher — settled in Chicago. They resumed their careers there, thanks to a connection Gottlieb had established between the Vienna research institute and the Chicago dental schools in the mid-1920s.

Gottlieb charted a different course, one that would eventually lead him to Dallas. He first traveled east to Palestine in an effort to recreate the research institute at the university at Tel Aviv, but the war’s impact reached there, too, and Gottlieb decided to seek a different option.

Immigrating to the U.S., he spent a brief time at Columbia University in New York and as a visiting scientist at the University of Michigan before receiving an offer from the Dallas dental school’s Dean Frederick Hinds to join the faculty. A group of alumni in Dallas reportedly contributed funds to bolster Hinds’ salary offer.

The appointment in Dallas created a permanent position for Gottlieb and remedied dental students’ impending shortfall in basic science instruction as a result of Baylor College of Medicine’s move from Dallas to Houston in 1943. The dental and medical students shared such courses, and the medical school’s departure meant the loss of most of the basic science faculty.

Gottlieb in Dallas

The absence of medical faculty mirrored a lack of adequate facilities on the campus.

This pre-eminent scientist, who had fostered incredibly productive research among his team in Vienna, arrived to deteriorating buildings that were prone to basement floods and had never been designed for dental education, much less research. The dental college shared medical school space for basic science lectures and technique laboratories, and its clinical building a few blocks away was a hand-me-down as well.

To exacerbate the situation, medical school personnel stripped the scientific instruments and supplies from the laboratories, even removing most of the electrical and plumbing fixtures as they left.

Somehow Gottlieb created a space to continue his work.

If he had lived longer he would have seen marked improvement. The college’s first specially constructed clinical facility opened in 1950, the year of his death at age 64, and a new wing devoted to basic sciences was completed in 1954.

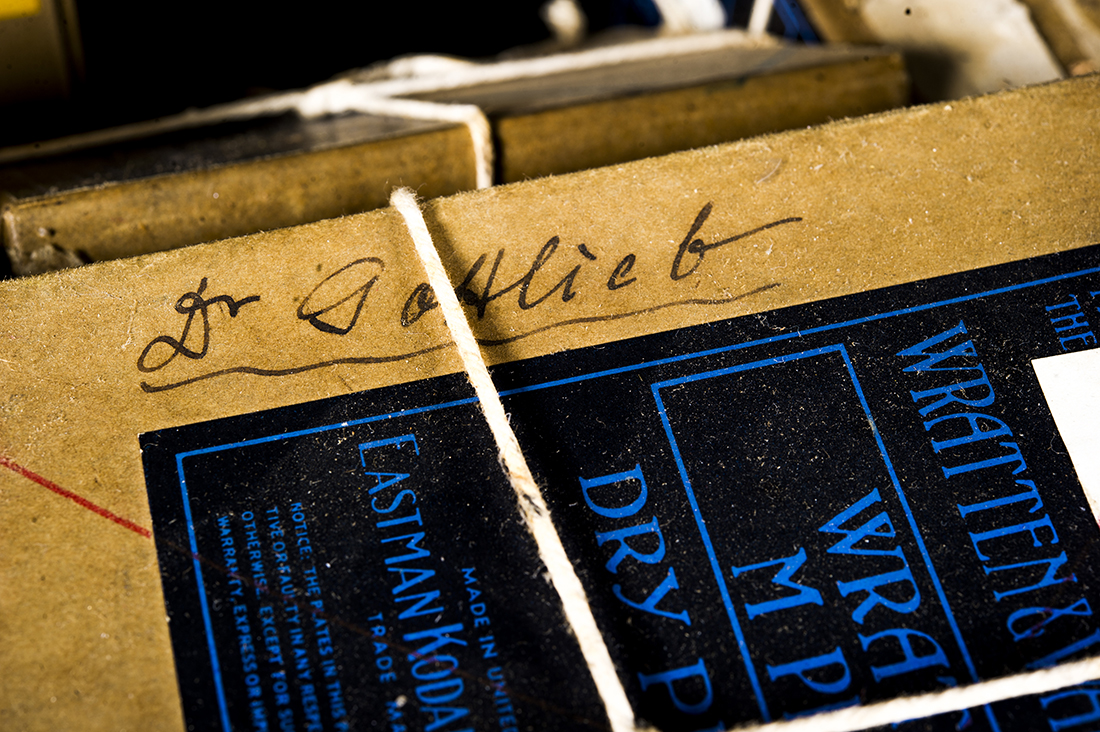

Remnants of Gottlieb’s research and materials continue to occupy various nooks and crannies within the building, resurfacing only to be moved again, leaving a crumb trail of information about his tenure at the dental school.

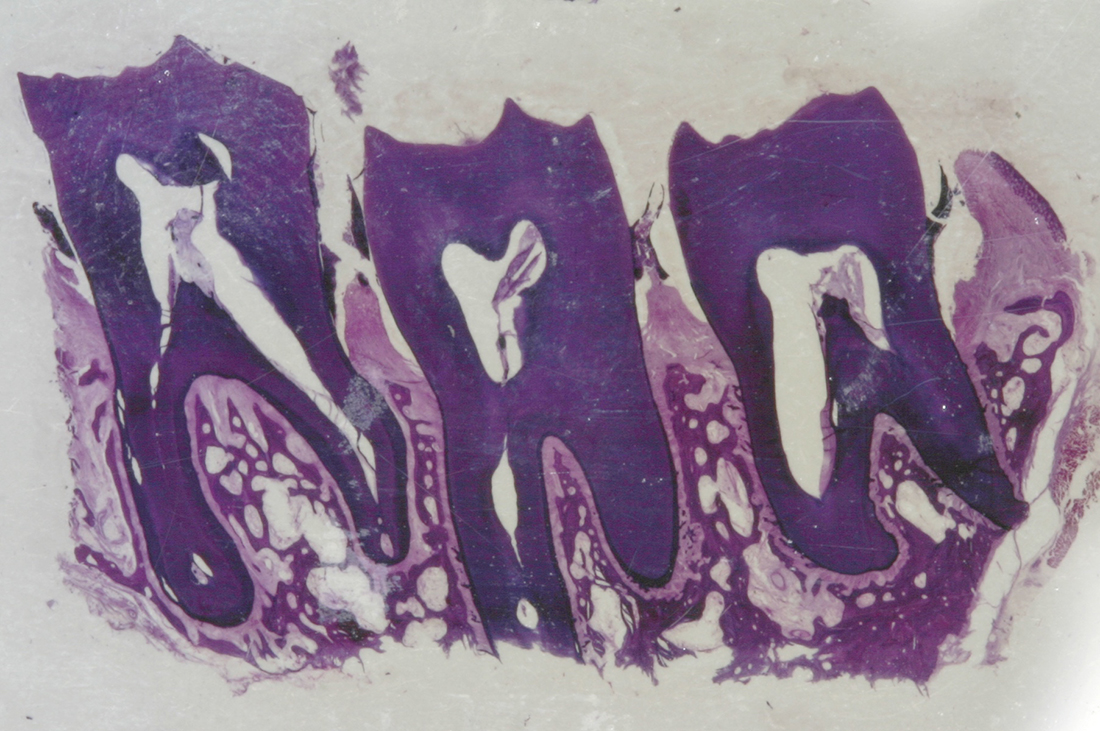

The most remarkable evidence of Gottlieb’s presence in Dallas is his collection of histological specimens. Some are tucked alongside his radiographs deep within the Baylor Health Sciences Library, where they are contained in wooden boxes and large black trunks marked with the initials “BG,” which journeyed with him across the Atlantic. The specimens’ remarkable quality has endured for decades.

“I made a digital program for the oral histology lab where students didn’t have to do microscopes or slides anymore, and I included quite a few of Dr. Gottlieb’s slides,” says Dr. James McIntosh, professor emeritus in biomedical sciences. “They had tremendous teaching value. Because the slides were too valuable to hand out to students — they were so big and can break easily — they weren’t used until faculty members Drs. Walt Davis and Ruth Jones made microfiche cards of select images in the early 1980s.”

Then there are the histological dyes from a German company that Gottlieb used, which Diekwisch stumbled across in one of the college’s laboratories in the 1990s. It marked Diekwisch’s first awareness of the presence of a distinguished histologist at the dental school, a clue that led him to uncover the story of Gottlieb’s final years in Dallas.

“Chroma makes by far the best histological dyes, so I thought there must have been an expert here,” says Diekwisch, who was born and raised in Germany. “I inquired, and then people started to bring Gottlieb material to me because they knew I spoke German and could read it.”

“Gottlieb and his colleagues were the ones who changed dentistry from being a technical shop into one that was scientifically based. If we had not gotten these physicians from Vienna, we would not be where we are today.”

—Dr. James Gutmann

The memorabilia came with stories, and Diekwisch collected an earful from former students — including the late Dr. Robert V. Walker ’47 — as well as others who acquired anecdotes about this brilliant professor secondhand. Walker had worked with Gottlieb for a year as a lab technician while attending dental school.

“Dr. Walker said he was impressed with Gottlieb,” Diekwisch says. “Dr. Walker recalled him being very tough on students because he had high expectations, maybe higher than the students were used to.”

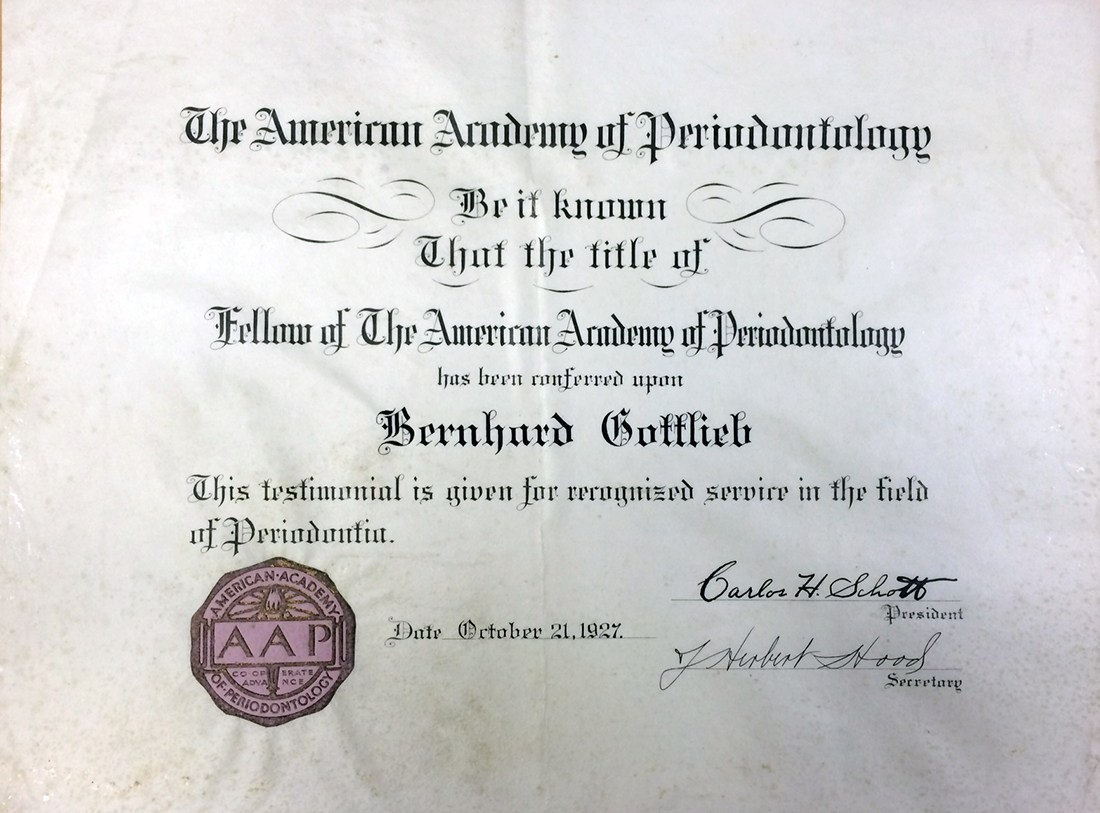

Over the decades, as faculty members vacated offices, new occupants discovered Gottlieb’s awards and certificates in drawers and closets, evidence of the esteem of this internationally known scientist, who worked in comparative isolation once he arrived in Dallas.

Gottlieb holds the dental college’s highest honor: membership in its Hall of Fame. He was one of the first two inductees, entering the ranks posthumously in 1982 alongside W.W. Caruth Jr., benefactor and namesake of the Caruth School of Dental Hygiene. Boelsche followed quickly with his own selection to the Hall of Fame in 1985.

Gottlieb’s broader influence

Thought Gottlieb transplaned to Dallas in 1941, his influence on American dentistry predates World War II by more than a decade.

Dr. William Logan, dean of Loyola University’s dental school in Chicago, met Gottlieb in Geneva in 1925 at a planning meeting of the Federation Dentaire Internationale, which hosted an International Dental Congress every five years. Designed for the exchange of research discoveries and clinical advances, the 1926 congress was slated for Philadelphia, with Logan as chair.

Knowing the international prestige of the research institute in Vienna, he invited Gottlieb and his associates to attend the Philadelphia meeting. The papers they presented reflected their characteristic meticulous attention to detail and foretold the precision they would bring to dental science in America after they immigrated.

After the meeting, Gottlieb traveled to Chicago with Logan, who aspired to establish a research program at Loyola. He asked Gottlieb to recommend an individual to lead that effort, to which Gottlieb suggested one of his exceptional institute colleagues: Orban.

Dr. James Gutmann, professor emeritus in endodontics and president of the American Academy of the History of Dentistry, studied Gottlieb’s life and work in 2012 for a paper detailing his impact on endodontic practice. Though he knew the scientist’s prestige, the scope of Gottlieb’s efforts was a discovery.

“I think it’s important to convey the true impact he had on so many things we are working with today: resorption during orthodontic tooth movement, endodontic procedures during root canal therapy, knowledge of periodontal disease,” Gutmann says. “Gottlieb and his colleagues were the ones who changed dentistry from being a technical shop into one that was scientifically based. If we had not gotten these physicians from Vienna, we would not be where we are today.”

The histology collection and its impact

The universal truth about Gottlieb’s work is the precision of his illustrations — those famous glass slides.

For McIntosh, the detail was paramount for teaching.

“It was very unique for the time because he embedded the sections in plastic and stained them after mounting on the glass,” McIntosh says. “These slides never faded; the color was vivid.”

Dr. John Wright, Regents Professor and department head of diagnostic sciences, describes the histologic specimens of teeth, tooth formation and even entire sections of the jaw as “marvelous.”

“For its time there was nothing like it. His collection was absolutely meticulous,” Wright says. “No one knew how to make sections like that. It was the preeminent collection in the world.”

Boelsche and the endowed chair

As Gottlieb’s slides have endured, so too will his legacy at the college through the new Bernhard Gottlieb Endowed Chair in Craniofacial Research.

Boelsche’s desire to honor this eminent scientist has come to fruition at last.

“Dr. Boelsche would be pleased to no end to know this chair now exists, and that it will let Gottlieb’s name live on at our college,” Eggleston says. “And this wasn’t even Dr. Boelsche’s school!”

Boelsche graduated at the top of his class from the University of Texas School of Dentistry at Houston in 1927 after attending Texas A&M University, where he was a member of the Aggie Band and Corps of Cadets. He later served as president of the American Academy of Restorative Dentistry, American Academy of Gold Foil Operators and Houston District Dental Society.

“Dr. Boelsche was an incredible dentist,” says Eggleston. “I became his patient when I was 12 and had broken my two front teeth while playing football. When he saved them, that made me want to become a dentist.”

Boelsche and his wife, Ida, had no children, and Eggleston became what was akin to their adopted son.

“I started practicing with him in 1972 in the Niels Esperson Building in downtown Houston,” Eggleston recalls. As one of that building’s first occupants in the late 1920s, Boelsche would walk up to his office on the 10th floor because the building had no elevators.

“I guess you could say I’m the ‘grandson’ of Dr. Gottlieb in dentistry,” Eggleston quips. “I’ve benefited so much from these two men.”

In 1979, after more than 50 years of practice, Boelsche and Ida created a charitable remainder trust with nearly half a million dollars in assets that would provide them with lifetime income and eventually support research activities in Gottlieb’s name at the Dallas dental school.

Boelsche died in September 1993, and his wife passed away the following spring. Quarterly disbursements from the trust continued until the entire balance was eventually distributed to the college, providing the foundation for the Gottlieb endowment. The funding for the chair was completed with a gift from Baylor Oral Health Foundation and matching funds from the Texas A&M University provost’s office.

Diekwisch was announced as the first holder of the endowed chair at a Feb. 20 campus ceremony.

“The Bernhard Gottlieb Endowed Chair in Craniofacial Research represents an important milestone for the college as we look toward building a stronger research enterprise and securing our position as a leader in dental education,” says Dr. Lawrence Wolinsky, dean.

“It is fitting that the first holder is an internationally renowned researcher and the director of our Center for Craniofacial Research and Diagnosis who also happens to have spent significant time studying Dr. Gottlieb’s life’s work.”

Diekwisch, who has used some of Gottlieb’s slides in publishing his own research findings on the origin of cementum, is inspired to emulate the chair’s namesake.

“I intend to honor this scientist’s memory by creating an environment that bridges the domains of basic science and clinical research to engage interdisciplinary researchers in answering questions that then lead to more questions — in the tradition of Gottlieb,” he says.