Progress notes

It was Christmas week in 1974. Dr. Charles Berry, then an assistant professor in microbiology, and his wife, Sandra, were driving along Interstate 30 just outside Dallas. They descended a hill, a straight, long stretch, with no guardrails separating the east and westbound lanes.

He watched in horror, hands tightening around the wheel, as a car that had just passed them sped several hundred yards ahead before drifting across the median, slamming into an oncoming vehicle. A third vehicle, a 1968 Ford pickup, crashed into the wreckage. When Berry pulled up behind the accident, he found both drivers from the head-on collision dead at the scene. The pickup was on its side, and on the pavement next to it, an elderly woman lay moaning for help. The truck’s other occupant, the woman’s son, had just picked her up from the hospital, the two nearly to their destination. While the son survived the accident, he was incapacitated in the moments after the crash and unable to come to her aid.

Berry knelt by the woman’s side, but with no medical training, he could do little more than offer words of comfort.

“I didn’t know what to do,” Berry says. “The ambulance came; the police came. They said, ‘What did you see?’ I told them what I saw.”

Berry left the accident scene with new resolve: If he ever found himself in a similar situation again, he would know how to provide immediate medical aid. He took his first CPR class with Dr. Fred Williams, a faculty member in what was then the Department of Physiology, who encouraged Berry to take the CPR instructor course, and from there, the instructor trainer course.

Soon the skill transitioned into a volunteer role with the American Heart Association. He was asked to serve as a national committee member, head up rewriting the organization’s standards for CPR instruction.

This extramural experience helped Berry feel more at ease working on committees. So much so, that he accepted appointments at the college without hesitation and even ended up working on every single committee served by the Office of Academic Affairs. After a five-year stint as vice chair of the Department of Biomedical Sciences, Berry went on to lead academic affairs. It’s a role that’s filled 17 of his 43 years on the faculty at Texas A&M College of Dentistry.

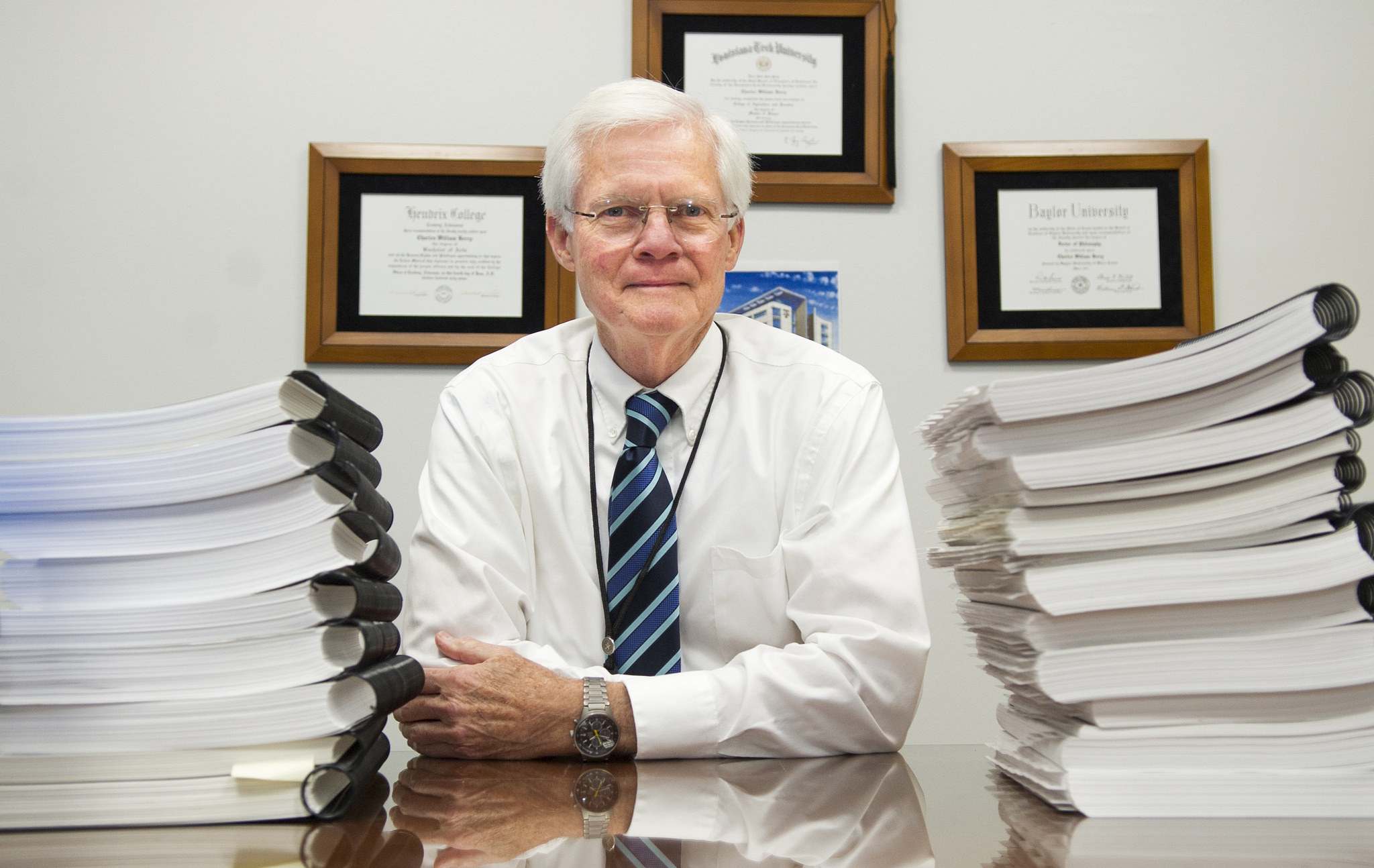

Now Berry has transitioned into a new post as a special assistant to the dean. His primary responsibility: coordinate the self-study for the 2018 Commission on Dental Accreditation site visit.

Intensive planning has already begun, and while Berry is at the helm, he points to the role of all of the dental school’s faculty and staff in making reaccreditation a reality.

“It’s a collaborative effort. No one person, not the steering committee, not the subcommittee chairs, makes it happen,” says Berry. “Everyone has a part in defining what we’ve done over the last seven years.”

Now he talks to us about hot-button topics in dental education accreditation and how dental research and academic affairs — the two focal points around which he has built his career — aren’t as different as many may make them out to be. In fact, they’re complementary.

Dentistry Insider: You’ve played an active role in seven accreditations for our college by this stage in your career. Having that kind of perspective and hindsight, what shifts would you say you’ve seen in requirements for dental education throughout the last few decades? What areas of demonstrated proficiency are gaining increasing traction?

Berry: If you talk about what has gained traction in dental education and what the commission is looking for, it’s assessment of competencies above everything else.

Telling is not teaching; listening is not learning. Students learn by doing. We can have a curriculum that has everything in it, and we can present that curriculum, but how do we know if the students have learned the contents of that curriculum unless we assess them, and how do you assess them? One of the most common ways is, you give a test, or you have a lab project, or you have a patient in the chair, and you have a procedure done, and it’s critiqued.

In our situation competence is always expected. That’s the starting point, so then the student will have notations made on the improvements that they need to make. Guess what the result is: We graduate very clinically proficient, competent dentists. Have been for a long time, still do.

Dentistry Insider: The self-study preparation associated with our fall 2018 CODA site visit is intensive, to say the least. You’ve already started the process two years in advance. Even with this in mind, if you could boil down the importance of CODA into just a few words, what would they be?

Berry: It validates that a program selected by the applicant is credible. The accreditation is necessary for a program of dentistry to get approval by the Department of Education to award degrees.

Dentistry Insider: For more than half of your 43 years on the faculty here, your emphasis was on microbiology instruction and research. How did you parlay that background into heading up academic affairs?

Berry: I can remember giving my presentation to the faculty when I was competing for the position, and Dr. Tommy Gage and Dr. John Wright were sitting next to each other. And I saw John Wright raise his hand and ask me a question. He said, “You are applying for an academic dean position in a dental school, but you’re not a dentist. How are you going to know how to solve the problems that are related to dentistry?” I said, “John, I know who to ask the questions to solve the problem.” The best answers are made with the best questions, so if you want to get something solved, get someone who knows what they are talking about.

There’s a very large sense of satisfaction in getting things done. It’s not for me; it’s for the institution and the people in it.