Progress notes

Oral cancer examinations: ensuring the knowledge and attention they deserve

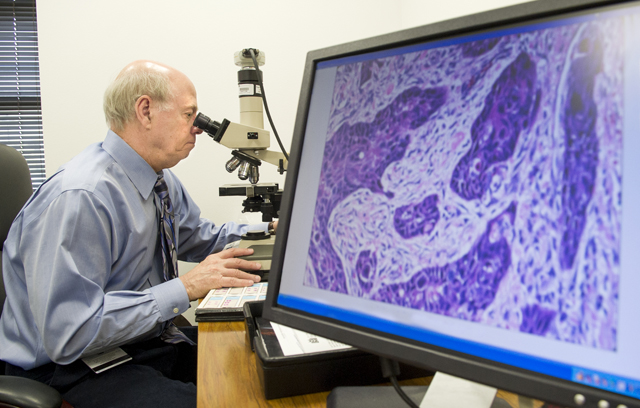

Regents Professor Dr. John Wright is a dentist by profession, but as an oral pathologist he spends significant time with physicians.

This diagnostic sciences chairman is accustomed to balancing both health care worlds. Faculty appointments at Baylor University Medical Center at Dallas, UT Southwestern Medical Center/Parkland Memorial Hospital and the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in Shreveport allow Wright to work on head and neck cases with staff and residents in general pathology, dermatology and dermatopathology. Rarely does a day go by that oral pathology doesn’t receive a consultation request from medical colleagues.

At continuing education events — such as the college’s 2014 Center of Excellence Conference on March 29, where Wright will discuss oral diseases and conditions common in underserved patient groups — he loves getting one question in particular: “Not infrequently, someone will come up and ask where I went to medical school,” says Wright. “I love to tell them that I’m a dentist, and what I do is the practice of dentistry. Particularly when lecturing to physicians, most of them have never heard of an oral pathologist. They are really shocked that a dentist would know as much as we do about disease.”

In this column, Wright imparts some of that knowledge on the subjects of oral cancer examinations, risk factors for underserved populations and just what patients should expect at routine dental appointments.

NewsStand: As someone who has collaborated with physicians and medical residents for more than 30 years, would you say evaluating patients for oral cancer is a responsibility that dentists and physicians currently share? If not, should it be?

Wright: The more people who are evaluating our patients for these conditions, the better it’s going to be for the public. Having said that, years ago there was a survey in The New England Journal of Medicine of medical school curriculum in the U.S., and it showed the average medical student got one hour of instruction about mouth problems. The irony is for every student who gets two hours there is another who gets none. This is woefully inadequate for physicians.

The real impact comes from the dental side, since we are the only health profession that adequately educates our students about these diseases. It’s an area for improvement on the medical side, and it would serve the public better if medical students were more knowledgeable about oral cancer and oral health in general. Many of my referrals come from physicians. They are aware that they don’t know much about the mouth, and they’re thrilled they can refer those patients to us.

NewsStand: Should patients expect oral cancer examinations as part of their dental appointments?

Wright: Every six months when patients come back for routine recall exams, they should get comprehensive oral examinations. Dentists are responsible for the oral health of their patients, and that includes more than just the health of their teeth and gums. It’s everything, including but not limited to, oral cancer. Dentists should tell patients why they are examining them, what they are looking for and the result of their examinations. I think dentists are doing a decent job of screening for oral cancer, but patients are often unaware of what their dentists are actually doing. Dentists should use the examination as an opportunity to educate their patients on what they are looking for and to reassure them that at this time they don’t have any features of oral cancer. It’s also an opportunity to educate them about early features of oral cancer and its risk factors.

NewsStand: What should patients know about optional oral cancer diagnostic tests above and beyond the visual inspections provided in biannual exams?

Wright: There is a variety of what we call adjunctive oral cancer screening devices. The research to prove efficacy of all of these devices was done by the companies that made the devices, and when they all came on the market they sounded wonderful. With independent testing, none of them has proven to be as effective as we thought.

I think all of these devices are on the right track. If nothing else, they have brought a lot of attention to oral cancer, which is positive, but none of them is the panacea the companies suggested they would be when they were brought to market. There is no substitute for a little bit of knowledge about this disease and the dentist being willing to spend the time to examine the patient.

NewsStand: When it comes to oral cancer diagnoses, what are some of the biggest differences between patients from underserved populations and patients receiving regular oral health care?

Wright: The primary cause of oral cancer is an abuse of tobacco and alcohol. We see that more often in underserved populations. They are probably a little more at risk.

Plus, the ability to survive oral cancer after treatment is directly related to its stage at diagnosis and its size. Underserved patients do tend to be more advanced by the time they are ultimately diagnosed. If you have an early oral cancer, and your dentist discovers it because you just happened to have an appointment and get screened, you’re one of the early stage cancer patients, and you survive. The underserved are not going to get picked up at that stage, which means they will ultimately not do as well.