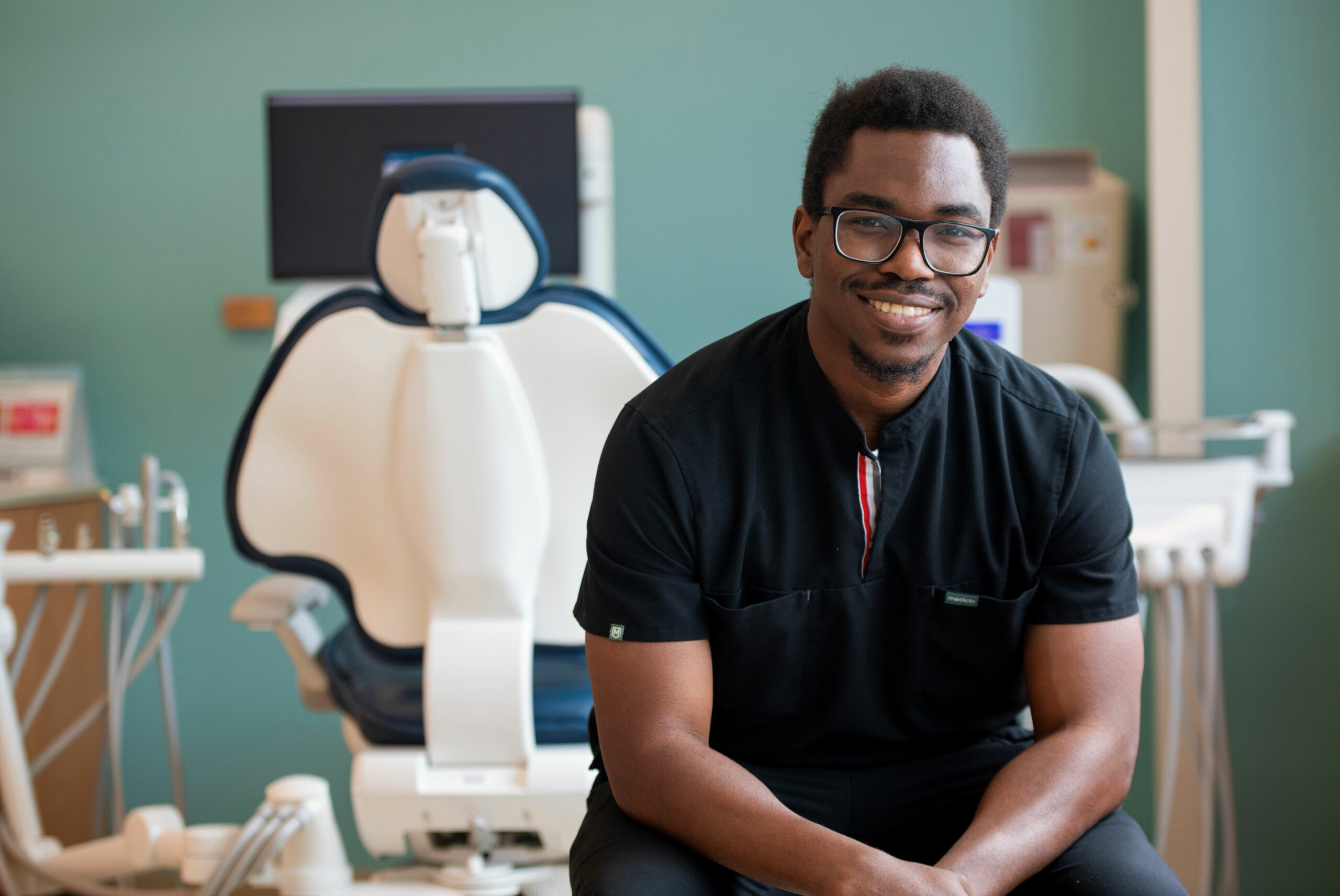

Story behind the smile

Shimirimana Eliya’s childhood was plagued with pain.

By age 3, his mouth was riddled with tooth decay, but with little knowledge of oral healthcare and no access to dental treatment in his home country – Tanzania – he was facing chronic deterioration.

Often unable to eat or sleep, he stared at the night sky, wondering what was wrong with him. He never dreamed that one day, not only would he have answers, but he’d also be pain free and providing dental care and treatment to others.

Inspired by his personal experience and decade-long quest for care, Eliya pursued a degree in dental hygiene and is a 2023 graduate of Texas A&M University School of Dentistry.

“With every pain I felt and experience that I went through, it made me become interested in the field of dentistry,” he said. “I was wondering if this only happened to me, why it was happening and how I could prevent it.

“That is why I’m here: because I believe prevention is key and knowledge is indisputable.”

Life in Africa

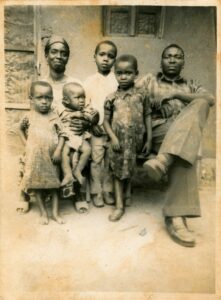

Eliya, one of 12 siblings, was born to Rehema Ndayisenga and Bamba Dieudonne in a refugee camp in Tanzania after the family fled war and genocide in Congo.

“I have vivid memories of what I would do every day,” Eliya said. “I didn’t know anything about having things you wanted or desired, but I had everything that I needed. I made the most of everything, and it never seemed like I needed anything. I had everything.”

Eliya said when he was not at school, he helped his mother and grandmother farm small plots of land, planting rice and picking up sugar cane. They often started at 6 a.m., returning around 5 p.m. so his mother could prepare the evening meal.

“In African countries where they have a lot of babies, those children later help produce food and help around the house,” he said. “If I wasn’t doing that, I would be at school.”

Eliya said they did not study their own language in school but were instead taught French because neighboring countries were colonized by Belgium. As people fled to Tanzania from those countries, they brought the language with them.

“There are multiple languages being spoken in one area,” Eliya said of the refugee camp. “You learn a lot of languages because your neighbor does not speak the same language as you. You learn a foreign language at school, and at home you’re learning your actual language and culture.”

In addition to French, Eliya learned to speak Swahili, Kirundi and Kinyarwanda.

Eliya began having problems with his teeth when he was a toddler. His family and community knew little about oral health and virtually nothing about dentistry. He later learned he suffered from severe tooth decay and gingivitis, but as a little boy, all he knew was that it hurt and he was desperate for relief.

“It was the kind of pain that was persistent,” he said. “A sharp pain, that even if you wanted to go to sleep, you couldn’t. You would just have to stay up with your eyes open, just staring at the wall, wishing you couldn’t feel it and wondering what life would be like without it.”

On more than one occasion, his parents sought treatment for him, including making a trip to a dental mission several hours from their home. After walking for hours and standing in line all day, Eliya and his mother were turned away when the clinic ran out of supplies.

“Although I was sent home, I was never upset because I had hope that they would return,” he said. “I just thought, I’ll wait until next year.”

But next year held no promises. Also, his family was nervous about divulging his problems publicly because officials could use it as a reason to delay their immigration to the United States. At least once, his mother took him to a hospital when the pain was especially severe, but because they knew little about dentistry, he was simply prescribed pain meds.

“When we went from Tanzania to a camp in Kenya, the problem got a little worse because I was bleeding when I was brushing my teeth,” he said. “The pain was too much for me to be able to sleep, but I just kept hiding it the same way they told me to.

“It’s just something that I had to deal with. They also took me to church to pray for it, and it helped as well.”

Moving to the U.S.

Eliya said the night his family was notified they would be going to the United States was memorable.

“Everybody was sitting on mats, eating food, and this man came and told us the news,” he said. “Getting that invitation was exciting because not a lot of people were able to. We knew the process would be long and exhausting, but it was exciting.”

In September 2007, Eliya and his family arrived in Texas, and they were awestruck by all the vehicles and tall buildings.

“All I could think was ‘there are a lot of moving cars!’” he said. “We come from a place where there’s not a lot of cars and not a lot of buildings. I wondered how do all these things work? How am I going to be able to learn this language and adapt to all these things?”

They were one of the first refugee families to move into their Fort Worth apartment complex, and most of their new neighbors were Hispanic, creating a bit of language confusion.

“When we first got here, we thought Spanish was English, and we started learning a little Spanish,” Eliya said. “We watched telenovelas and Telemundo, so when we went to actual school, we spoke a little Spanish, rather than English.”

Eliya’s elementary school was a designated language center with students from around the world, and the curriculum was taught at a slower pace as the children learned English at the same time.

It was a gradual process. In addition to school, Eliya had an English tutor, and he learned a lot watching PBS Kids every morning.

“The language barrier wasn’t frustrating to me,” he said. “I took it as a challenge to learn and just be able to get to where I needed to be.”

Eliya and his family lived in the U.S. for about year before he was able to see a dentist.

“I was in fifth or sixth grade when I went to the dental office for the first time,” he said.

The visits became more frequent in sixth and seventh grade, and by eighth grade, he was becoming increasingly frustrated.

“They were filling cavities, and I started questioning things,” he said. “They were doing the same things over and over, just filling cavities, never educating me about brushing, flossing and how diet plays a huge part in cavity formation.

“Again, I was left in the darkness, not knowing why this was happening,” he said. “Living in an underprivileged neighborhood in the U.S. was not entirely different from Africa.”

By ninth grade, Eliya was considering a career in dentistry with the hope he’d learn more about his own issues and be able to help others. He was now pain-free but still didn’t fully understand why he had so many dental problems. As a student at Amon Carter-Riverside High School in Fort Worth, he convinced an AP teacher to help him get into honors classes.

“I felt like I was able to learn more because they expected a lot,” he said. “In the language center, they were glad you were there, but I didn’t want to ‘just be there.’

“The honors classes were more challenging, and at first it was hard to catch up and be in a space where everyone thought differently, and they were already accustomed to the language,” he said. “But it was something I wanted to do, and I just put every effort into doing so.”

Eliya graduated high school in 2017 and went on to play soccer at Centenary College of Louisiana in Shreveport where he earned a Bachelor of Arts in Biology.

“It was constant work, but I loved every moment of it because I love playing soccer. I knew what my goal was, and I knew what I had to do to get there,” he said. “Playing soccer really helped me refresh my mind, so that when I got off the field, all my focus was on studying and getting the grades I needed to get to [dental hygiene school].”

Eliya was accepted to four dental hygiene schools, but his interview with faculty convinced him to attend Texas A&M School of Dentistry.

“Being on the Zoom call with [Executive Director Leigh Ann] Wyatt, Professor [Lisa] Mallonee and other professors, it felt like family,” he said. “The interview was more like a conversation, and I chose to come here because I knew that I would get the education I need with faculty who cared and did not see me as just another number.”

Wyatt said she and the other faculty members wanted Eliya for the A&M program as soon as they met him.

“Even though the interview was short, we could sense so much about him,” she said. “I could not see the class of 2023 without Shim. I wanted to be part of his story, his journey, and I knew all the other students in the class would be better for time spent with him.”

Throughout his coursework, he treated patients at the A&M clinic, and last summer he returned to Africa, volunteering in a dental clinic in Zambia.

“The continent was as if I left it yesterday,” he said. “I was excited to provide care for the people of Ndola because not so long ago I, too, was in a line where they were, hoping someone would give me an answer to my questions and pain.”

Eliya said they treated as many people as they could, but even so, some people were turned away at the end of the day.

“I just wanted to work faster and faster,” he said. “It was painful … every time I saw someone leave without receiving treatment, I saw myself in them, but I’m proud of the team I was working with over there; we made the most of the resources we had.”

Following graduation, Eliya hopes to secure a job in public health enabling him to continue providing treatment and education in underserved communities here and abroad.

“I’m grateful to Professor Wyatt and the dental hygiene faculty and staff for making this dream a reality and equipping me with the tools and skills necessary to become a great hygienist,” he said. “This program has allowed me to finally achieve my dream of working in public health and traveling abroad to further expand oral health.”