The way Claude Williams sees it

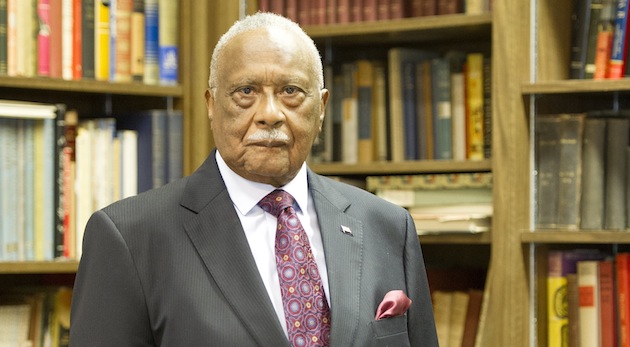

The college’s first African-American faculty member is retiring after 40 years. These are the stories you haven’t heard.

It was 1969. As a practicing general dentist in Marshall, Texas, Dr. Claude Williams clearly saw the reality that one of his 9-year-old twin daughters needed braces. There was just one problem.

“Not a white orthodontist would treat her. Nor would a dental school,” says Williams, now director of community outreach at Texas A&M University Baylor College of Dentistry. Williams took his daughter to Houston. San Antonio. Dallas. The answer was the same. An orthodontist in Fort Worth — a former Navy comrade — put it bluntly: “Claude, if you want your daughter to have orthodontic treatment, you are going to have to go back to school.”

As an African-American dentist in a state with deep-seated segregation, Williams had a built-in client base and burgeoning practice. At the time, life was good for him and his wife and three children. They had just moved into their dream home — a ranch house they designed.

Williams didn’t waste any time leaving it all behind.

He called the dean at Howard University, his undergrad and dental school alma mater. One slot remained in the university’s graduate orthodontic program — only in its second year at the historically African-American institution.

There was just one catch: It was January, and the residency would start in July.

“I had five months to establish a whole new way of living and move my family to Washington,” says Williams. “It was divine providence. The only position available in orthodontics in the country was there at that time.”

And so the general dentist who didn’t have any intentions of pursuing a specialty left that barely-lived-in ranch house and shuttered his practice. Selling it wasn’t an option. After all, says Williams, who would buy a black practice in East Texas?

“Could you imagine having a daughter who needed orthodontic care, and no one would treat her?” Williams says. “I had to re-evaluate a lot of things in my life. How do you respond to the rejection? It can either elicit a negative response or a positive response.”

More than 40 years later, in a conference room at the American Dental Association headquarters in Chicago, Williams recounted that same story to more than 75 dental association presidents, past presidents and student leaders from across the country.

By the time he was done, the audience had dissolved into tears.

“There wasn’t a dry eye in the house, to convey the kind of story that he did,” says Dr. Nathan Fletcher, a National Dental Association past president, who asked Williams to speak at the ADA-sponsored 2010 diversity summit.

“Some found it incredulous. Some probably were in disbelief,” says Fletcher. “But when you have a man standing at the podium telling his life story you really can’t deny the fact and verification of it.

“I think that that story is kind of the epitome of who he is. He saw the bigger picture and generated legacies for other people, primarily African American, to get into the profession and be successful. That’s not a story that a lot of people know.”

Much can happen in 40 years.

When Williams joined the college’s faculty in 1973 as an assistant clinical professor in the orthodontic department, his role had nothing to do with diversity initiatives or community outreach. But as the first African-American faculty member at a Texas dental school on the cusp of integration — not to mention the first African-American orthodontist in the entire Southwest — Williams was thrown right into the thick of things.

It wasn’t long before Baylor College of Dentistry integrated. One by one, minority students began seeking him out in the clinic, even showing up at his private orthodontic practice in South Dallas.

“Bringing in more black students and minority students without proper preparation of the faculty, staff and students caused conflicts,” says Williams. “They were brought in with no support. They had a very difficult time.”

In Williams’ typical fashion, he did something about it.

Perhaps the origins of the school’s pipeline programs, designed to lead students from underrepresented minority groups to careers in dentistry, began on weekend afternoons when Williams — who was only on campus a half-day a week — invited students to his office to get personal instruction from African-American lab technicians.

In the years that followed, Williams formed what was then the Office of Minority Affairs with support from administration and then-dean Dr. Dominick DePaola. The role took Williams out of the orthodontic department but allowed him to shape the early direction of what is now known as the Summer Predental Enrichment Program. In the years since, the program has evolved under the careful guidance of the Office of Student Development and Multicultural Affairs, helping to make the dental school one of the most diverse in the country.

All of Williams’ efforts zeroed in on one goal: increasing access to care for those in underserved areas — those who, decades before, may have been in situations painfully similar to his daughter.

“Everything I have done since the beginning has been toward that cause,” says Williams.

Williams used his local, state and national connections to forge long-lasting partnerships for the college. Such has been the case with the Emmett J. Conrad Leadership Program, for which the college hosts an annual graduate and professional school seminar.

For years during Black History Month, Williams saw to it that students, faculty and staff had the opportunity to hear notable speakers from the African-American community — household names, like Fox 4 News Anchor Clarice Tinsley; Fort Worth Star-Telegram Columnist Bob Ray Sanders, a longtime professional journalist; Dallas Mavericks President and CEO Terdema Ussery; and retired University of Texas at Dallas President Dr. Franklyn Jenifer, also a former president of Howard University.

Williams also brought TAMBCD into the community.

Dr. James Cole, dean emeritus, went with Williams on several visits to Dallas movers and shakers, including elected officials’ local offices.

“If there was something that we needed to resolve at the state level, Claude could really help in that way,” says Cole. “Whether they were state representatives or senators, it was obvious he had known those individuals and their staffs for years.”

The car rides provided ample time for Williams to share his stories from decades past. He’d tell Cole about what it was like trying to get into Dallas country clubs or even shop for a car.

“Before then I’m just not sure that I appreciated the depth of segregation and what it was like for Claude and others,” says Cole. “It was an education for me, because of his experiences.”

Along the way, Williams mentored and counseled minority students as they navigated the mires of dental school.

“I don’t think I would have made it through dental school without him,” says Dr. Angela Jones ’01, who maintains a private dental practice in Dallas’ Oak Cliff. “He was the most helpful person at Baylor for me. He always listened; the door was always open.

“Whatever I needed he was there. Dr. Williams went to bat for us. He always went to the source.”

His influence went beyond the college — to the farthest reaches of the globe even — like in 1995, when Williams traveled to the Third African – African-American Summit in Dakar, Senegal, located on Africa’s western tip. He was one of just six U.S. dentists invited.

This June, Williams spoke during an American Dental Education Association workshop. The topic: how to use storytelling as a leadership tool. He addressed the new dental program recipients of the ADEA/W.K. Kellogg Foundation Minority Dental Faculty Development Grant, from which TAMBCD received funding between 2004 and 2010.

“He’s kind of a legend,” Dr. Jeanne Sinkford, director of ADEA’s Center for Equity and Diversity, says of Williams. “We used his stories to talk about his experience early in life, and how that impacted his motivation and how it changed the direction in his life.”

Sinkford’s ties with Williams go back to their undergrad days at Howard University, where she later became the dental school’s first female dean.

“His past experiences with racial prejudices interfered with his career and his practice,” she adds. “We were trying to get the younger people who have the challenges he had to understand that the issue is bigger than race. It’s important to institutional growth and institutional quality.”

There’s power in those stories, the ones that take Williams from small-town life in Marshall and childhood summers on the family farm in Jefferson, Texas, to lonely days at the U.S. Naval Training Center in Bainbridge, Md., where he integrated the Navy Dental Corps — and found his second passion in golf. From Texas to Maryland and Washington and back again there is one common thread: motivation borne of adversity.

When asked about his Aug. 31 retirement, Williams says, “I don’t ever consider, ‘Where do I stop?’

It’s about, ‘Where do I go on the next level?’ This is not the end.”

There is more to Williams’ story. Read about it in the fall 2013 Baylor Dental Journal.