Why I teach: Part 3

Texas A&M College of Dentistry’s faculty members are universally dedicated. With multiple career options, what motivates someone to become a dental school professor? Is it a purposeful process or an unexpected discovery? A visit with a few A&M dental school instructors yields a variety of journeys with one common realization: the incomparable rewards of working with students and guiding them to their academic goals. The following is Part 3 of a multi-part series.

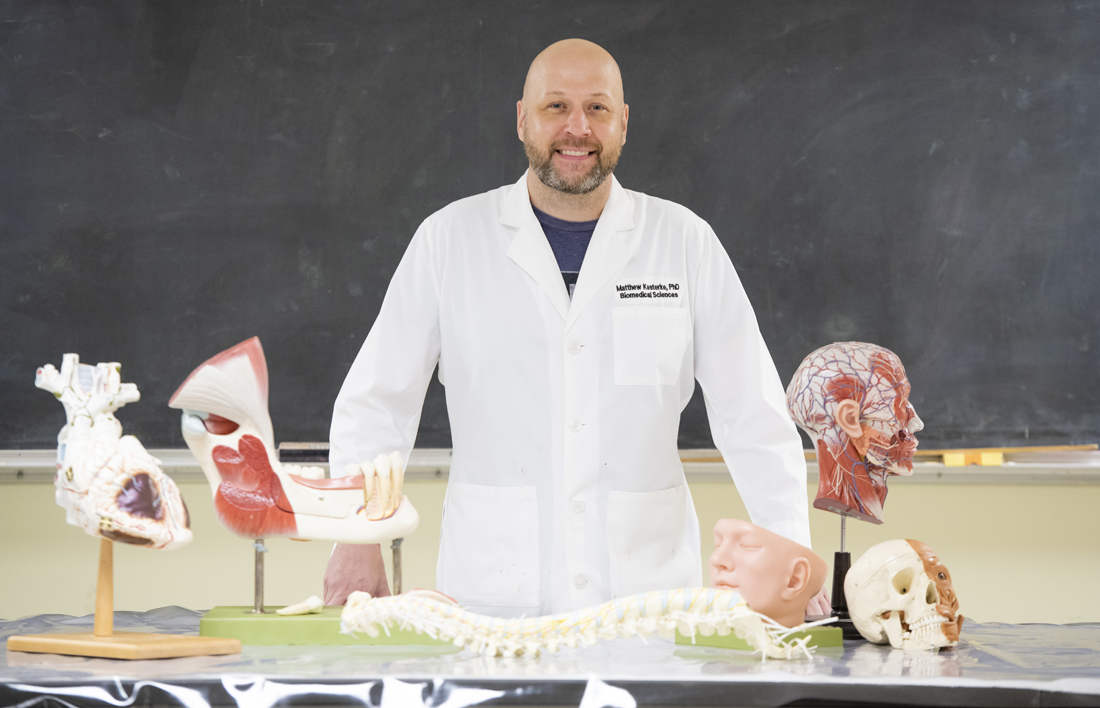

Dr. Matthew Kesterke

Bones hold special fascination for biological anthropologist Dr. Matt Kesterke, who never tires of pursuing the stories they can tell.

Bones hold special fascination for biological anthropologist Dr. Matt Kesterke, who never tires of pursuing the stories they can tell.

First-year dental students benefit from his instruction in the gross anatomy course, but education was not part of Kesterke’s career plans 16 years ago when he began working as a coroner in Laramie, Wyoming, while completing his master’s degree.

“I was finally doing forensics like I wanted,” he says, “working a lot with law enforcement. My original research was forensic anthropology – I was going to be solving crimes, CSI level. You were going to see me on TV,” he laughs.

As it happens, he got asked by the county coroner to teach a course for police officers at the Wyoming Law Enforcement Academy on how to identify common bones—as human vs. elk, for example— how to communicate with families on death calls and whom to call regarding any unattended death or crime scene investigation.

“That was my first experience with teaching and I really enjoyed it,” he says.

A career in dental education first became a blip on his radar when he was a doctoral student at the University of Pittsburgh several years later, where he discovered how the anthropology program’s anatomy basis intersected with the health sciences. He began teaching gross anatomy with a mentor and other professors and simultaneously strengthened his own expertise by participating in anatomy courses with medical and dental students. This reinforced for him the alignment of forensics with health care.

“Everyone thinks forensics is CSI, but it’s really a study of normal biological variation,” he says. Teaching gross anatomy from this growth and development perspective aids health professions students, he explains.

“It gives a better understanding of how to approach clinical treatment,” Kesterke says. “You can’t define abnormal if you don’t know what normal is.”

As an instructional assistant professor in the Department of Orthodontics, Kesterke devotes extra time to coaching individual students through the “deer in the headlights” aspect of that first semester, guiding them through sticking points and helping them prioritize study efforts that strengthen specific weaknesses.

“Our students recognize the privilege of being able to work with human donors,” he says. “A lot of programs don’t still do that. I love teaching here because health professions school students are universally dedicated.”

No one was happier to see Kesterke in his element than his mom, who passed away in December 2021. A retired high school math teacher, she was “over the moon excited” when he decided to teach, he says, and asked about his lectures and students often.

The dental school is a great fit for Kesterke, who “saw a whole bunch of potential mentors and colleagues here”—names he cited in his dissertation on the growth and development of the cranial base.

“The selling point was seeing all these anthropologists being encouraged to teach what they wanted to teach while doing research they wanted to research,” he says. “Here I can do both; we can use research to effect positive change in the clinical environment.

“I’ve been fortunate to have wonderful mentors, and my goal is to emulate that. No one teaches you how to mentor; you learn as you do it and try your best to emulate what works for you.”